The Jazz style was created in the 20th century, by black artists, in New Orleans, Louisiana, and has since expanded into different forms.

Early jazz performers such as Louis Armstrong and Jelly Roll Morton improvised over these ragtime and blues traditions, resulting in a wholly distinct style of American music.

Ragtime and jazz syncopations were developed by reducing and simplifying the sophisticated, polyrhythmic polymetric layered and polymetric patterns.

It can be seen in all West African ceremonial dance and group music for over a century. The earlier accentuations of numerous vertically competing meters were reduced to syncopated accents.

One distinguishing element of jazz over other conventional musical forms, mainly classical music, is that the jazz artist is primarily creative.

Whereas classical instrumentalists often articulate and express someone else’s work. Jazz is primarily created spontaneously, and it necessitates many specialized and unique procedures.

Many so-called solos in jazz were written themes judged vital and integral to the work and its execution.

Pre-History of Jazz

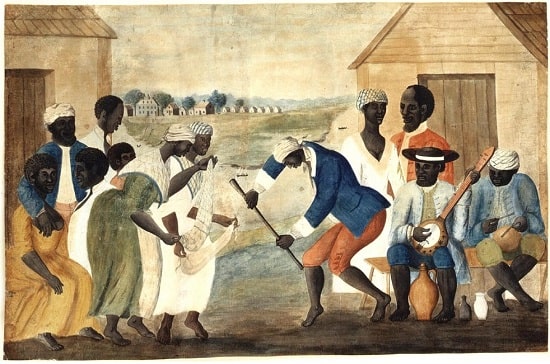

Enslaved individuals were rooted in West Africa, where rich musical traditions were passed down to America’s slaves through songs and field chants.

Many enslaved sought work as musicians after slavery was ended and exposed them to various musical traditions worldwide. Such as European classical and folk music traditions.

Jazz arose from this emerging world of independence and liberty, fostering a culture of experiment and expression that would become essential to the genre.

Slave camps, Christian churches, and religious gatherings throughout the South were melting pots of African and American musical forms long before jazz existed.

The work songs, screams, and field hollers which were a part of life in Africa were preserved in memory and maintained when enslaved people were transferred to the New World as Africa has an oral music tradition.

By the late 19th century, these ancient song forms had evolved and adapted to their new surroundings, including aspects of European music in their performances in some instances.

The genesis of jazz, which occurred in the early years of the 20th century, involved such cross-fertilization of musical cultures.

However, African artists and musicians had already had a long history of influencing American cultures and music by this time.

During the 18th and 19th centuries, three musical styles arose in America due to the mingling of European and African musical traditions. Each had a significant effect on the development of jazz.

Spirituals, ragtime, and blues were all developed to satisfy their musicians and audiences; each found its method of combining European and African traditions.

But they all had one thing in the standard: they were all distinctly American styles.

Jazz Music with African and European influences

The elements that make jazz distinctive derive primarily from West African musical sources as taken to the North American continent by enslaved people. Enslaved Black people came from diverse West African tribal cultures with distinct musical traditions.

These, in turn, encountered European musical elements such as dance and entertainment music and shape-note hymn tunes.

The rhythmic and structural elements of jazz derive primarily from West African traditions. At the same time, European influences can be heard in its use of conventional instruments such as Trumpet, trombone, saxophone, string bass, and piano.

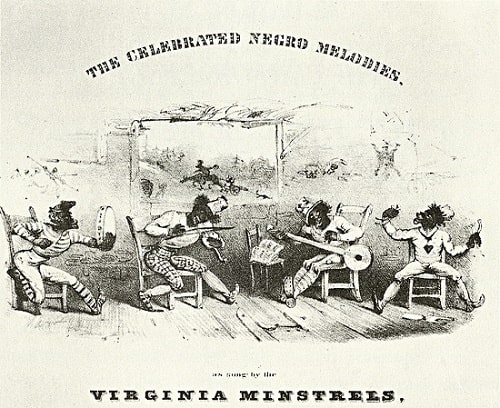

The jazz syncopations were not entirely new and could be heard even earlier in minstrel music. They resulted from reducing and simplifying the complex, multilayered, polyrhythmic designs indigenous to all kinds of West African ritual dance and ensemble music.

The former accentuations of multiple vertically competing meters were also drastically simplified to syncopated accents.

Jazz melody evolved out of a simplified residue and mixture of African and European vocal materials. It was intuitively developed by enslaved people in the 1700s and 1800s.

The widely prevalent emphasis on pentatonic formations came primarily from West Africa. The diatonic (and later more chromatic melodic lines of jazz grew from late 19th- and early 20th-century European antecedents.

Harmony was most likely the final feature of European music that Blacks adopted. Harmony, once mastered, was applied to religious texts as a musical resource; one outcome was the gradual creation of spirituals.

It was also borrowed from white religious revival gatherings that even African Americans in several parts of the South were pushed to attend.

The creation by Blacks of the so blues scale, with its “blue notes“—flatted third and seventh degrees—was a significant result of these musical acculturations.

Early in the 19th century, many black artists learned to play European o, notably the violin, and they used to imitate European dance music culture in their cakewalk dances.

European-American minstrel show artists in blackface, blending syncopated rhythms with European harmonic accompaniment, popularized the song abroad.

Rhythms and tunes from Cuban and other Caribbean locations were translated into piano salon music by Louis Moreau Gottschalk in the mid-1800s. New Orleans served as a significant crossroads for African-American and Afro-Caribbean cultures.

Max Harrison describes jazz as a “composite matrix” made up of various vernacular components that came to collide at various times and in diverse places.

The cotton plantation field hollers; railroad, river, and levee work songs; hymns and spirituals; brass band, funeral processions, and parade music; dance music; banjo performing tradition, which culminated in the banjo’s enormous popularity half a century later; wisps of European opera, theatre, and live performance music.

Survival of African rhythms

According to jazz expert Ernest Borneman, “Afro-Latin music,” comparable to what was performed mainly in the Caribbean, predates New Orleans jazz around 1890.

An essential rhythmic figure found in many distinct slave music of the Caribbean and Afro-Caribbean traditional dances seen in “Souvenirs from Havana” (1859) is the three-stroke pattern known as tresillo in Cuban music.

Tresillo is the most fundamental and widely used duple-pulse rhythmic pattern in Sub-Saharan African and African Diaspora music traditions. It was brought to America via the Atlantic slave trade during the colonial era.

The tresillo is the most basic duple-pulse rhythmic cell in Cuban and Latin American music. It was brought to the New World via the Atlantic slave trade during the colonial period. This pattern is by far the most basic and standard duple-pulse rhythmic cell.

African Americans were fortunate to get military surplus bass drums, snare drums, and fifes after the Civil War. A distinctive African-American percussion and fife music arose, containing tresillo and similar syncopated rhythmic patterns.

This was a different drumming tradition from its Caribbean rivals, exhibiting a distinctively African-American worldview.

“The bass and snare drumming musicians performed irregular cross-rhythms,” said writer Robert Palmer, who speculated that “this cultural practice must have traced back to the latter 19th century, and it might not have formed in the first place unless there hadn’t been a depth of polyrhythmic complexity in the society it supported.”

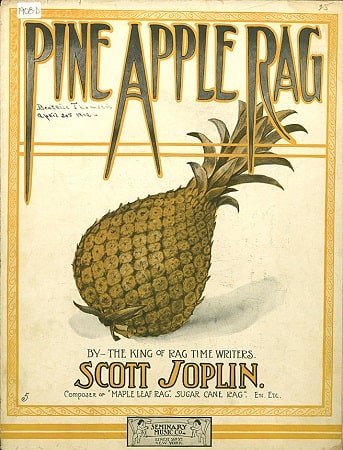

Ragtime in Jazz Music History

Ragtime is generally composed in 2/4 or 4/4 time, with a dominant left-hand sequence of bass lines on solid beats and harmonies on weak beats (beats 2 and 4) and a syncopated theme in the right hand.

According to some accounts, the word “ragtime” comes from the right hand’s “ragged or syncopated cadence.” A “ragtime waltz” is a rag composed in 3/4 time.

Ragtime was first published as sheet music in 1895 and was popularized by African-American performers such as singer Ernest Hogan, whose hit tunes were published the same year.

Vess Ossman produced “Rag Time Mix,” a combination of these tunes as a banjo solo. In 1897, composer William Krell released “Mississippi Rag,” the first composed piano instrumental ragtime work.

African-American composer Tom Turpin wrote “Harlem Rag,” the first rag produced by an African-American.

Cuban Influences

In the 19th century, when the habanera achieved an international appeal, African-American music began to include Afro-Cuban rhythmic patterns.

New Orleans and Havana’s musicians would play on the twice-daily boat between the two cities, and the habanera swiftly spread across the musically rich Crescent City.

According to John Storm Roberts, the musical style habanera “arrived in the United States 20 years before the very first rag was written.”

The habanera was a persistent feature of African-American distinguished music tradition for more than a quarter-century, wherein the ragtime, cakewalk, and proto-jazz were creating and evolving.

Habaneras were the first published music rhythmically built on an African motif, and they were generally available as sheet music.

The “habanera rhythms” (also referred to as “congo”), “tango-congo,” or tango, from the standpoint of African-American music, can be compared to a tresillo with a backbeat.

The habanera was the earliest of several Cuban music genres to gain popularity in the U.S, reinforcing and inspiring African-American musicians to adopt tresillo-based rhythms.

Jazz Root in New Orleans

In 1718, the French Louisiana community established New Orleans as a region. In 1763, the Louisiana provinces were given to Spain, but France took them in 1803.

In the Louisiana Purchase, France nearly quickly sold the province to the United States. Rather than being Protestant and English-speaking, Creole society was Catholic and French-speaking.

The town’s culture was enhanced not just by European influences but also by African influences. Enslaved West Africans made up 30% of New Orleans’ population in 1721.

At the end of the 17th century, persons of diverse African heritage, both free and slave, accounted for more than half of the city’s population. Many migrated via the Caribbean, bringing West Indian cultural customs with them.

After the Louisiana Purchase, English-speaking Anglo- and African-Americans stepped into New Orleans. Partway because of the cultural friction, these newcomers started settling upriver from Canal Street and the already full French Quarter (Vieux Carre).

These settlements grew the city boundaries and made the “uptown” American sector. Many German and Irish immigrants arrived before the Civil War, and the number of Italian immigrants rose afterward. Many were educated in France and performed in the best orchestras in the city.

Mardi Gras Indians were black “gangs” whose associates “masked” as American Indians to honor Native Americans. African dance in Congo Square ended before the Civil War; drumming and call-and-response chanting were part of early jazz.

New Orleans music was also influenced by the popular musical forms that increased throughout the U.S. post-Civil War, such as ragtime and brass bands.

New Orleans music was also influenced by the favored musical forms that increased throughout the United States following the Civil War.

In the 1880s, brass bands in New Orleans, such as the Excelsior and Onward, were mostly made up of officially trained musicians who read complex scores for concerts, parades, and dances.

“Papa” Jack Laine’s Reliance Brass Bands were integrated before segregation pressures increased. A unique collaborative association developed between brass bands in New Orleans and mutual aid and benevolent societies.

After the Civil War, such associations took on special meaning for emancipated African-Americans who had limited economic resources. Dance bands and orchestras cushioned the brass sound of Creole of color music.

String dancing groups were prevalent in more formal settings around the century. The brass bands’ instrumentation and musical section playing increasingly affected the dance bands, which changed in orientation from string to brass instruments. These transformations ultimately united black and Creole musicians.

Early jazz was encountered in neighborhoods all over and around New Orleans – it was a regular part of community life. Neighborhood social halls, some conducted by mutual aid and benevolent societies or other civic organizations, were often the sites of banquets and dances.

Jelly Roll Morton, creative piano stylist and songwriter began his odyssey outside New Orleans before 1907.

The Original Creole Orchestra, with Freddie Keppard, was an influential early group that left New Orleans. Chicago and New York became the central platform for New Orleans jazz.

Sometime before 1900, African-American community organizations known as social aid and pleasure clubs also began to spring up in the city.

In 1917 the Original Dixieland Jazz group cut the first commercial jazz recording while playing in New York City. The charm of the New Orleans sound knew no boundaries.

In 1922 Louis Armstrong was summoned to Chicago by King Oliver, his mentor, and led a revolution in jazz. Armstrong replaced the polyphonic ensemble style of New Orleans with the development of the soloist’s art.

Louis Armstrong’s recordings in the 1920s and 1930s are milestones in the progression of jazz as we know it today.

Jazz became the unchallenged famous music of America during the Swing era of the 1930s and 1940s. Latest innovations, such as bebop in the 1940s and avant-garde in the 1960s, departed further from the New Orleans tradition.

After the small-band New Orleans style fell out of fashion, attempts were made to revive the music by Bunk Johnson and George Lewis.

Conclusion

Jazz is a uniquely American musical genre that emerged in the early twentieth century. Many Afro-American ethnic music cultures are rooted in spirituals, labor songs, and blues.

It also drew inspiration from 19th-century band music and the ragtime keyboard style.

Jazz is defined by its particular rhythm patterns, harmonic techniques that are similar to but not identical to functional harmony, and the technique of improvisation.

Classical European music and popular music have influenced and been inspired by jazz. The lines between things aren’t usually so apparent.

Despite its brief history, jazz has evolved into various diverse types that non-specialists need to be at least vaguely aware of.

The contribution of all influential jazz performers had branded the age of jazz in American history as the “Jazz Age.”